It began with a flyer slipped into hundreds of letterboxes. Six years later, Bangalow Koalas is a thriving volunteer network, close to planting half a million trees and stitching together a wildlife corridor across Australia’s Northern Rivers region.

This is a story about koalas, eucalypt trees and how fast nature can rebound when given the chance. But it’s also a story of human tenacity and connection — because Bangalow Koalas wouldn’t be what it is without co-founder Linda Sparrow.

“I’m a country girl. I grew up in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales. Our Vice President grew up in Wollongong. We’re a couple of bogans who happen to be running a charity,” she says with a laugh.

This down-to-earthness is undoubtedly part of Bangalow Koalas’ appeal. “I think people are comfortable around us because we’re genuine and we’re passionate. I am just me, and I don’t try to be anything else. I’m most happy when I’m out in the field, talking to amazing, wonderful people who’ve become friends,” Linda says.

“We’re bringing together everyone — individuals, families, communities, Indigenous groups, farmers, schools — in a collaborative effort that shows change is possible,” she explains.

“We all care about each other, we all care about the planet, and we care about koalas.”

“I need your help saving the koalas”

Before Linda was known for her conservation work, she was known for getting things done, which is why, in 2016, she got a call from a friend who said “I need your help saving the koalas”.

At first, “saving the koalas” meant stopping development on a nearby 400-metre strip of trees. Under NSW planning rules, land can only be considered — and protected — as core koala habitat if koalas have been recorded locally, either at the time of assessment or within the past 18 years. But “up until that point, the Byron Council only had two recorded sightings of koalas in the whole of Bangalow,” Linda explains.

So she teamed up with an ecologist at Byron Council and dropped flyers that asked ‘have you seen koalas, past or present?’ Reports poured in, and the trees were saved.

She then did another letterbox drop, this time asking for volunteers to help clear weeds from Crown land near the now-protected habitat. “Twenty people turned up with their whippersnippers and shovels and kids, ready to clear the weeds from the base of these trees. We put on a sausage sizzle too,” she recalls. The sense of possibility was palpable. “We thought: oh wow, we’re onto something here”.

At first, most plantings were in Bangalow itself. With a population of about 2,700 people, Linda handled the letterbox drops herself — “though some of those hills are a killer,” she says. But as the project expanded into the wider Byron Hinterland area, she recruited the help of a neighbour, who would drive the car while she dropped the flyers. “We did thousands of drops. Jumping in and out of the car was killing my back,” she says. “But we were getting the people coming along!”

By 2019, the effort had snowballed. Two major plantings that year drew about 70 people each. “It was lucky it was on a big property, because there were so many cars! It was all over in less than an hour,” she recalls. “We planted 2,000 trees in 45 minutes.”

“We’re not going to wait”

Koalas live in eucalypt forests throughout eastern and south-eastern mainland Australia, eating leaves that are toxic to almost every other animal.

Thanks to a slow metabolism and a specialised gut and liver, koalas are able to break down the toxins in eucalyptus leaves and squeeze out every bit of energy, giving them near-exclusive access to this food source. But koalas aren’t the only ones who benefit. By thinning the canopy in patches, koalas help shape the forest, letting light reach the ground and encourage understorey plants and diversity.

But these forests — and the koalas that call them home — are under increasing threat.

In 1992, koalas were listed as Vulnerable in New South Wales. In May 2018, the state government released the New South Wales Koala Strategy, aiming to coordinate efforts to protect and recover koala populations.

But in the summer of 2019–2020, fire tore across Australia on an unimaginable scale. More than 24 million hectares burned, and an estimated three billion animals were killed or displaced. Among them were more than 60,000 koalas, according to a WWF-Australia report. Impacts ranged from death and injury to smoke inhalation, dehydration and trauma, as well as the destruction of food and shelter. Surviving koalas then faced increased predation and conflict as they fled into unburnt forested areas.

In 2020, a Parliamentary Committee found that without urgent intervention, “the koala will become extinct in New South Wales before 2050”. Among the committee’s recommendations was the creation of a Great Koala National Park (GKNP) — an idea first floated by environmental groups in 2012.

But for Linda, the bushfires were a brutal reminder that neither humans nor koalas have time to spare.

“The bushfires really drove me. People were phoning me from all over New South Wales, and from overseas, asking how they could help. It was almost like it was my job to try and keep people’s faith, to reassure them that it would be okay,” she says.

“It just made me go, ‘that’s it, we’re not going to wait, we’re just going to push ahead, we’re going to do it.’”

In 2021, the NSW Greens introduced a bill to establish the GKNP, but it was voted down by the Coalition Government and Labor Opposition. Two years later, Labor went to the state election with a promise to create the park, and after winning the election, committed $80 million to the park’s development.

During the assessment phase in 2024–25, logging continued in parts of the proposed GKNP (despite a limited pause in some ‘koala hubs’). On 7 September 2025, the government confirmed plans to combine existing reserves with 176,000 hectares of state forest to create a network of approximately 476,000 hectares. Funding was increased to $140 million, with an immediate, temporary halt to logging inside the park’s proposed boundaries and support packages for affected timber-mill workers.

“The Great Koala National Park is great news for koalas and other threatened species in the mid-to-north NSW coast,” Linda explains. “But up in the Northern Rivers, koalas are still under constant threat from native-habitat logging, disease, car strikes and dog attacks, so our job is never-ending.”

“It’s like a domino effect”

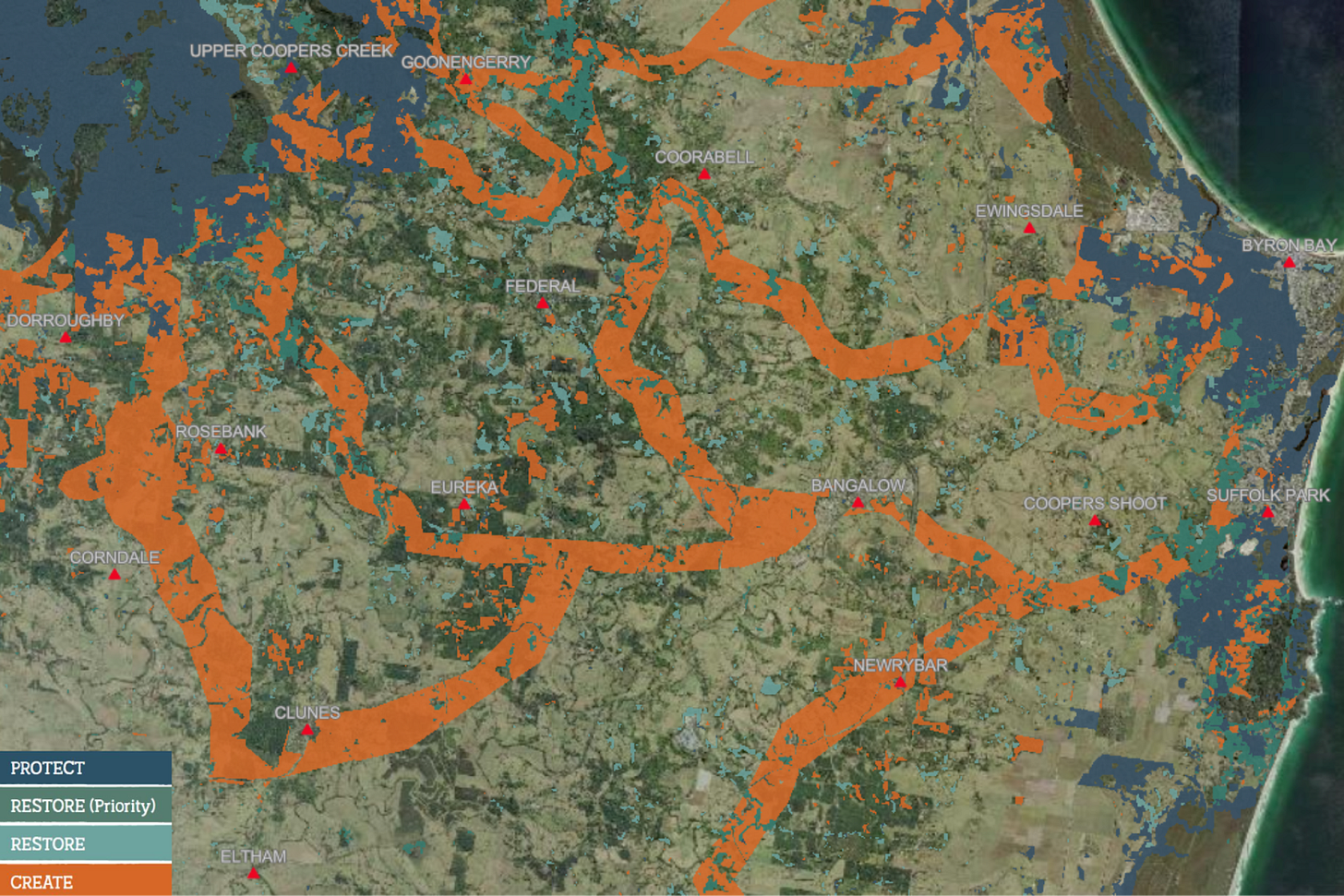

Bangalow Koalas is in the business of helping landholders help koalas. But the organisation is strategic, focusing its efforts where they’ll have the most impact by working with landholders inside the Northern Rivers Regional Koala Strategy’s priority areas for habitat protection, restoration and creation.

“We work with a lot of farmers,” Linda says. “They’re more than happy to give over parts of their land, because they can still have their cattle, they can still have their crops. They want to contribute. They know replanting trees actually benefits their farms.”

Once a landholder is on board and grant funding is secured, Linda works with an ecologist to design a tailored species list. Because most funding is tied to koala recovery, 60% of trees planted are koala feed trees, with the other 40% chosen to strengthen the ecosystem as a whole. “Every single planting is site-specific,” she explains. “If it’s a riparian area, for example, we’ll plant more rainforest species, closer together. We’re also planting species for glossy black cockatoos and to benefit grey-headed flying foxes, because without them we have no forests.”

Once the species list is set, seedlings are ordered from local nurseries and volunteers are mobilised. But planting is only part of the job. Four contracted companies then carry out maintenance on a three-monthly cycle, all scheduled and tracked by Linda. “We can’t continuously replant trees that don’t survive, but we do infill plantings at least once. A lot of the time we don’t need it. WWF says an 85% survival rate is good — and we average 90–95%, though extreme weather can wreak havoc with plantings.”

Then there’s the reporting side of the project. All plantings are photo-monitored, with reference posts marking three angles for before-and-after shots. “We know we’re doing the right thing because we can see it. Often, within 18 months, koalas are spotted in the new trees. In some plantings, after two years, the trees are 10 metres high.”

To keep track of all these moving parts, Linda uses a metre-wide, colour-coded yearly calendar. “People come in and see the planner and they gasp,” she says with a chuckle. “But it’s the only way I can manage getting all these trees in the ground. It’s very old-fashioned, but I am an old girl, and it works for me.”

At the top of Linda’s planner is a running tally of trees planted each year: 19,250 in 2019, 56,000 in 2020, 81,000 in 2021, 83,000 in 2022, 96,000 in 2023 and 78,000 in 2024. With each new planting, momentum builds. “Someone will plant, their neighbour will see, and it’s like a domino effect.”

At the time of writing, Bangalow Koalas have planted 470,757 trees — supported by grants from organisations including the Wedgetail Foundation.

“If you put in the right species, if you put in the hard yards, if you don’t give up, it pays off,” Linda says.

“500,000 reasons for hope”

Linda has her eyes on a milestone: half a million trees in the ground. “We’ve been writing every possible grant application we can to try and secure funds for this milestone. It’s so close,” she says.

But this number isn’t just symbolic, it’s strategic — because milestones inspire people, especially in the wake of disasters when many feel powerless.

“Back when the 2019-2020 fires were happening, and then the floods as well, people didn’t think they could make a difference. But I said: ‘You can make a difference. We can all make a difference.’”

“That’s why I really want to get to that 500,000 mark — because that would be such a good thing to get out to the media, to get out to people, to show them what is possible,” she says.

“You don’t have to be an ecologist, or a scientist, or a horticulturist, or anything like that. We’re just a small community group. You just have to be passionate, dedicated and determined.”

Linda calls this project “500,000 reasons for hope”. It’s about hope — for koalas and other native species, for ecosystems under pressure, for communities coming together, and for people themselves, she explains.